A broom hovers hesitantly around the perimeter of a mound of confetti-like paper on the floor of one of the corridors of MUŻA – the Malta National Community Art Museum.

A broom hovers hesitantly around the perimeter of a mound of confetti-like paper on the floor of one of the corridors of MUŻA – the Malta National Community Art Museum.

The caretakers are unsure what to make of this exhibit. They have been indoctrinated not to touch or disturb the artworks in the museum. But this is their territory. The courtyard and corridors on the ground floor of the museum, along with the toilets and reception area, are public spaces that they have been instructed to clean. Artist Sandra Zaffarese’s installations, however, won’t behave or comply with their notion of static artwork. The confetti, which substitutes for a mound of building material or can be found piled upon stone balustrades and shored up in corners, seem to have a mind and a life of their own. Conceived as reminders of ‘the eventuality of loss, erosion and human intervention’, the airborne confetti have a knack of displacing themselves from the terrain of their installation and posing a dilemma for the caretakers. ‘To sweep or not to’, that is the question.

‘All is not lost’ is one of nine installations participating in ‘No Ordinary Terrain’, a collective exhibition by artists Zaffarese, Aaron Bezzina, Keit Bonnici, and Tom Van Malderen, which will continue until 1st August. The exhibition tests the borders between private and public space, looks at land appropriation and occupation and explores what happens in the intermediary grey zone when a public arena such as the MUŻA corridors, courtyard and community space is handed over to a group of artists and is made private for a moment.

“It is very relevant for us to give life, purpose, and opportunity to public spaces that we think are useful but underused,” Tom, the mastermind behind the collective, asserts. “I have always been attracted to spaces that are less conventional,” he continues. Tom, who is Belgian and has been based in Malta for the last twenty years, wanted to gather a pool of artists who “like to think and work in a sculptural way” and whose previous output “had always looked at how people organise themselves in public spaces.”

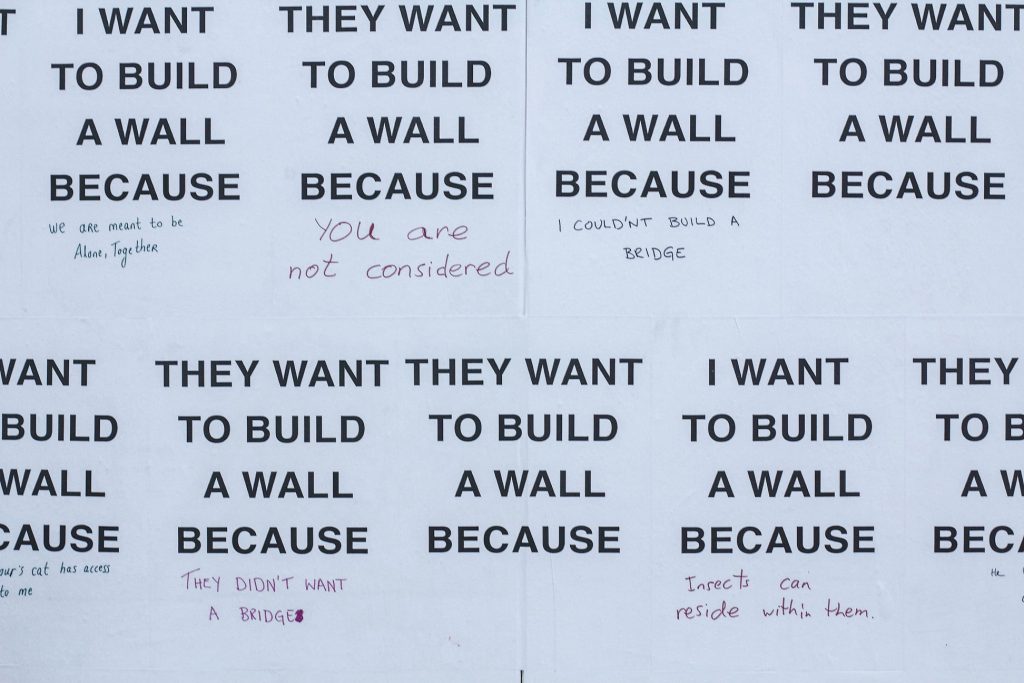

Visitors to MUZA’s courtyard are immediately confronted by a rubble wall topped by three metallic discs, which besides blocking the area, also partially obstructs the view of the fountain beyond. The positioning of the rubble wall built by Kyle Darmanin, a precise jigsaw puzzle of strategically placed stone with no cement or mortar, floats between being a work of art in itself, a moist, cool ecosystem for plants, reptiles, and insects, and a message. “Life is full of barriers. Walls are thematic of the relationships in our lives and how we organise our space. There is a contemporary obsession in art with overcoming barriers, but barriers also provide guidance and structure. An old saying states that it is better to build a wall than a war.” Tom quips.

Furthermore, the silver discs echo the oil drums previously placed upon the walls to block visibility and ensure privacy. The discs also bring to mind target practice and, by dint of this open association, hunting. The ambiguity is intentional. “If there is any function to art, then it is to give visitors the opportunity to think beyond a set of parameters, to let them make up their own stories. What I really like is to stimulate people’s minds.” Tom enthuses.

As a familiar and integral feature of the Maltese rural landscape, helping to prevent soil erosion and delineate topographic boundaries, rubble walls (ħitan tas-sejjieħ) generally have positive connotations, correlated as they are with pleasant countryside walks, nature, and a sense of belonging to place. By placing them within an institutionalised environment and contrasting two cultures through the use of the same local limestone – the perfect metric engineering of a Baroque edifice with the equally poetic stacking of a peasant wall- visitors are encouraged to reflect on the increasingly lost approach to landscape transformation.

As a familiar and integral feature of the Maltese rural landscape, helping to prevent soil erosion and delineate topographic boundaries, rubble walls (ħitan tas-sejjieħ) generally have positive connotations, correlated as they are with pleasant countryside walks, nature, and a sense of belonging to place. By placing them within an institutionalised environment and contrasting two cultures through the use of the same local limestone – the perfect metric engineering of a Baroque edifice with the equally poetic stacking of a peasant wall- visitors are encouraged to reflect on the increasingly lost approach to landscape transformation.

‘Too illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’ touches upon the more polemic issues surrounding land appropriation. With rampant over-building, and given the Islands’ minuscule size, the interplay between private and public space is increasingly contested. On the one hand, illegal structures such as boathouses and hunter huts are unsustainable, aesthetically debatable, and to a certain extent elitist because only a small percentage of the population uses them. On the other hand, hunting constitutes a form of bonding between father and son. “Eliminating the boathouses from the facade of the Valletta bastions or along St. Thomas Bay, for example, would similarly be doing away with the social constructs they facilitate and the cultural identity they represent.” So Tom, the creator of this particular installation, suggests. They have become intrinsically part of the Maltese landscape as much as the rubble walls.

‘Too illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’ touches upon the more polemic issues surrounding land appropriation. With rampant over-building, and given the Islands’ minuscule size, the interplay between private and public space is increasingly contested. On the one hand, illegal structures such as boathouses and hunter huts are unsustainable, aesthetically debatable, and to a certain extent elitist because only a small percentage of the population uses them. On the other hand, hunting constitutes a form of bonding between father and son. “Eliminating the boathouses from the facade of the Valletta bastions or along St. Thomas Bay, for example, would similarly be doing away with the social constructs they facilitate and the cultural identity they represent.” So Tom, the creator of this particular installation, suggests. They have become intrinsically part of the Maltese landscape as much as the rubble walls.

‘No Ordinary Terrain’ attempts to inhabit a “weak position within the grey zone” to address the often overloaded but topical debate of construction -the white elephant in the room- by “softening up these greed and development lusts and assuming a less polarised stance.” “We don’t have to stand on either side of this wall. People should be less scared of sitting on the fence,” Tom adds.

Aaron Bezzina’s ‘Floor Pieces’ takes this concept one step further. His art is anti-interactive. “I want to go back to do something that is observatory and conceptual rather than experiential. I am interested in people understanding artwork from a mechanical point of view without operating or understanding it. Once you have understood how it works, then you understand why the work exists,” he affirms. Aaron’s series of tiles in three sizes, one a traditional 20 by 20 Maltese tile, another a 30 by 30 terrazzo tile, and finally a contemporary tile measuring 60 by 60, are essentially foothold traps, their coiled spring mechanisms safely locked. By occupying part of the floor, they become part of the property, a statement of personal taste and ownership and a form of land demarcation. Inspired as he is by the floor art of Karl

Aaron Bezzina’s ‘Floor Pieces’ takes this concept one step further. His art is anti-interactive. “I want to go back to do something that is observatory and conceptual rather than experiential. I am interested in people understanding artwork from a mechanical point of view without operating or understanding it. Once you have understood how it works, then you understand why the work exists,” he affirms. Aaron’s series of tiles in three sizes, one a traditional 20 by 20 Maltese tile, another a 30 by 30 terrazzo tile, and finally a contemporary tile measuring 60 by 60, are essentially foothold traps, their coiled spring mechanisms safely locked. By occupying part of the floor, they become part of the property, a statement of personal taste and ownership and a form of land demarcation. Inspired as he is by the floor art of Karl Andre, Bezzina is preoccupied with the act of permission. “If something is displayed as a piece of artwork in a museum, what permission do you have to touch or interact with it? Should you be given a set of instructions?” Ironically for an anti-interactive installation, because Aaron has created a “showcase of a tile” and placed them in their natural habitat on the floor, not on plinths or on the wall, visitors have stepped on them, kicked them, so much so that the tiles have had to be moved to the side “if they were to survive the exhibition.”

Andre, Bezzina is preoccupied with the act of permission. “If something is displayed as a piece of artwork in a museum, what permission do you have to touch or interact with it? Should you be given a set of instructions?” Ironically for an anti-interactive installation, because Aaron has created a “showcase of a tile” and placed them in their natural habitat on the floor, not on plinths or on the wall, visitors have stepped on them, kicked them, so much so that the tiles have had to be moved to the side “if they were to survive the exhibition.”

Issues of confrontation and interaction also perplex the visitor when they come across Keit Bonnici’s Dancer, which can be found docked or wandering within the liminality of the corridors. The robot, which can be activated remotely from Keit’s cellphone, is a reflection of how artificial intelligence occupies and contests space in our lives. “I wanted to create a work that exists in movement. How could I occupy space through a robot? Am I part of someone else’s existence? Can I occupy space when not present?” he asks.

Join the debate and attend any of the two public talks and discussions on 17th July and on 24th July from 11:00AM till 1:00PM.

You can also meet the artists on 18th July between 11:00AM and 1:00PM

NO ORDINARY TERRAIN is supported by MUŻA and the Arts Council Malta’s Project Support Grant.

Published in the Times of Malta 23.07.21

By Warren Bugeja, Executive Communications, Heritage Malta

Up Next

News | 14th July 2021