Stepping into the fauces, it is cool and dark after the harsh sunlight outside. The client blinks and adjusts his eyes, and guided by the flickering candles of the candelabra makes his way to the atrium. He is not alone. Together with other clients, he will await his patron, the Dominus (master) of this household, to make his appearance in the tablinium (office), where the daily ‘salutatio‘ or blessing will be exchanged. Beyond the tablinium, just to the right, the client can just make out dappled shadows playing on the peristyle’s Doric columns, cast by the opening to the sky above.

Unless he has the good fortune to secure a dinner invitation, this client will never cross that invisible threshold marking the public and private spheres of this Roman townhouse.

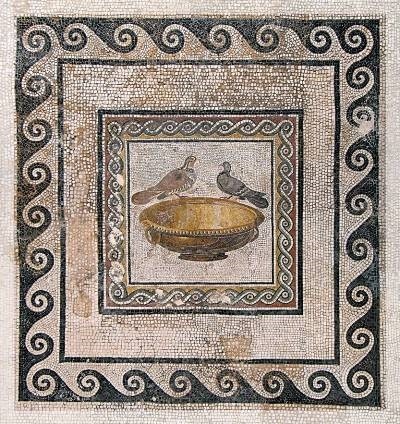

“Beautiful are the drinking doves whose head casts a reflection on the water of the cantharus (fountain)”

“Beautiful are the drinking doves whose head casts a reflection on the water of the cantharus (fountain)”

So wrote Pliny the Elder, in his Historia Naturalis, praising the artist Sosos from Pergamon (modern-day Anatolia) for his artistic skills. Replicated throughout antiquity, Sosos’ dove motif, on the central emblemata in the peristyle’s sunken mosaic impluvium at the heart of the Roman Domvs, continues to welcome the visitor several centuries later and signal that they have been accepted into the inner domestic sanctuary.

The peristyle’s functions were many. Besides being a source of water collection, it allowed light into the house and doubled up as an art gallery. The various layers of wall paintings illustrate that craftsmen were updating and keeping up with styles and fashions in Rome.

Unlike similar Roman abodes of the period, “the layout of the Dvmus Romana (Roman Town House) is atypical since it does not follow a straight line of sight from the fauces to the peristyle, which leads us to believe that the peristyle might have been a later addition,” comments David Cardona, Senior Curator for Phoenician, Roman and Medieval sites at Heritage Malta.

Unlike similar Roman abodes of the period, “the layout of the Dvmus Romana (Roman Town House) is atypical since it does not follow a straight line of sight from the fauces to the peristyle, which leads us to believe that the peristyle might have been a later addition,” comments David Cardona, Senior Curator for Phoenician, Roman and Medieval sites at Heritage Malta.

Built between 50BC and 50AD, the Dvmus is the only urban dwelling of its kind on the Maltese Islands. The other Roman domestic buildings, such as the rural farmsteads of San Pawl Milqi and Ta’ Kaċċatura or the Villa Marittima at Ramla Bay, do not exhibit the same richness of interior decoration and level of sophistication in architecture.

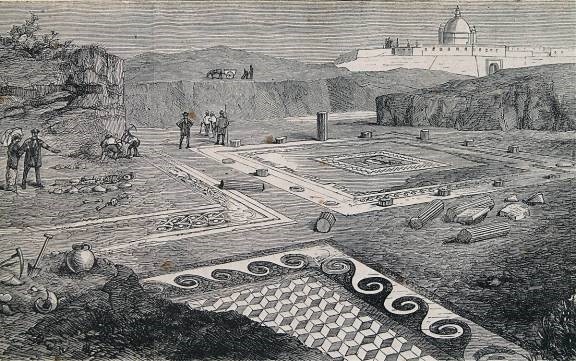

This February, the Domvs Romana is celebrating the 140th anniversary of the site’s accidental discovery when workers planting trees for Howard Garden came across some of the mosaics and Islamic burials in 1881. The milestone is sandwiched between two other anniversaries. One in 2020 marking the 100th anniversary of the commencement of excavations overseen by Sir Themistocles Zammit, at the rear and front of the current site entrance with its 1920 portico. And another to be celebrated next year, commemorating the construction of the museum building itself 140 years ago. Originally built to protect the mosaics and serve as a repository for all the Roman antiquities of the Island, the Domvs was the first museum erected on Malta.

This February, the Domvs Romana is celebrating the 140th anniversary of the site’s accidental discovery when workers planting trees for Howard Garden came across some of the mosaics and Islamic burials in 1881. The milestone is sandwiched between two other anniversaries. One in 2020 marking the 100th anniversary of the commencement of excavations overseen by Sir Themistocles Zammit, at the rear and front of the current site entrance with its 1920 portico. And another to be celebrated next year, commemorating the construction of the museum building itself 140 years ago. Originally built to protect the mosaics and serve as a repository for all the Roman antiquities of the Island, the Domvs was the first museum erected on Malta.

Antonio Annetto Caruana, the librarian of the Bibliotheca and curator of the archaeological collection housed in it, was immediately entrusted with clearing the peristyle and nearby mosaics from under a metre and a half or more of soil when the site was first discovered. The depth of soil, unusual in Malta, was a result of the site’s location, below a raised mound created by the Knights of St John and referred to as ‘the killing grounds.’ The higher terrain facing the ditch and Mdina bastions was deliberately left devoid of trees and buildings in order to leave potential besiegers exposed and vulnerable. The fact that no buildings were constructed enabled the discovery and subsequent excavations.

Several activities were planned to mark this triple anniversary, but unfortunately, Covid-19 put a spanner in the works. However, the limited museum opening times have enabled an overhaul in the way visitors experience the Roman townhouse. A series of new interpretation panels and screen displays will help shed further light on domestic aspects of everyday life in a Roman household, including ancient food and drink, makeup and hairstyles, clothing, and entertainment. One of the panels will feature a recorded interview of Lina Cardona, who, along with her sister and parents, found refuge in the domvs as a child during the Second World War. Lina, who is still alive, recounts how they were evacuated here from Ħal Tarxien when her father, a custodian of St. Paul’s Catacombs, asked permission from the then Director of Museums to take his family up to Rabat for safety. Keeping faith with tradition, Lina’s grandson also works as a Gallery Site Officer with Heritage Malta. Lina recalls conservators working on the titular altar painting of Ta’ Liesse Church when the ‘Roman Villa Museum’ was converted into an emergency restoration centre for paintings damaged by the bombing.

Several activities were planned to mark this triple anniversary, but unfortunately, Covid-19 put a spanner in the works. However, the limited museum opening times have enabled an overhaul in the way visitors experience the Roman townhouse. A series of new interpretation panels and screen displays will help shed further light on domestic aspects of everyday life in a Roman household, including ancient food and drink, makeup and hairstyles, clothing, and entertainment. One of the panels will feature a recorded interview of Lina Cardona, who, along with her sister and parents, found refuge in the domvs as a child during the Second World War. Lina, who is still alive, recounts how they were evacuated here from Ħal Tarxien when her father, a custodian of St. Paul’s Catacombs, asked permission from the then Director of Museums to take his family up to Rabat for safety. Keeping faith with tradition, Lina’s grandson also works as a Gallery Site Officer with Heritage Malta. Lina recalls conservators working on the titular altar painting of Ta’ Liesse Church when the ‘Roman Villa Museum’ was converted into an emergency restoration centre for paintings damaged by the bombing.

The anniversary upgrade of the Domvs also includes a project to replace the present peristyle skylight with a retractable modern replica of the 1880s version and install climate control units. Furthermore, visitors will be able to scroll through a tablet featuring a website that catalogues Roman Statuary in Malta, created by Profs. Anthony Bonanno in collaboration with Heritage Malta. The tablet will be positioned next to larger than life statues of the Emperor Claudius, his daughter Claudia Antonia and a statue of a child, identified by the bulla containing a protective amulet in the folds of his toga, most likely the Emperor’s adoptive son Nero.

According to David Cardona, “we can deduce that whoever lived in this Domvs, if not the Protos or Governor of the Island himself was well connected, besides being wealthy. He must have wielded some power. The procurement of marble was under the control of the Emperor and you would also have required his dispensation or that of his officials to display a statue of the Emperor and his family.” Once colonized in 218 BC, and the Punic wars concluded, the Maltese Islands may not have been as strategically important to the Romans as previously thought, but the fact that a personage of Cicero’s stature requested to be exiled here meant that it was not a backwater either.

Originally the ancient Roman ‘capital’ of Melite stretched from the acropolis and temple precinct of present-day Mdina to St. Paul’s Parish Church in Rabat. Mdina would have contained the largest number of public buildings, as many marble relics were found there, including a dedication concerning a temple to the god Apollo near the Benedictine monastery. A monumental marble statue of the Phoenician goddess Ashtarte, nowadays exhibited within the Domvs, once stood in a niche on the left of the entrance to Mdina. Later day passers-by would irreverently spit upon the statue on account of its pagan representation.

Although we may never know if the Medieval and Baroque palaces of Mdina conceal a Circus Maximus or an Amphiteatre -the 1693 earthquake alone left 5 metres of debris – four fields, some of which display possible Roman fortifications, remain to be excavated. Zammit cut two preliminary trenches in these fields, situated across the road, dug by the British in 1899, to the Museum railway station between Mdina and Mtarfa. ‘Melite Civitas Romana‘ is the name given to a series of excavations which have been postponed to later this year with the aim of discovering more about the ancient town. The project, a century on from Zammit’s last dig, is a joint collaboration between Heritage Malta, The University of South Florida (USF), and a group of Australian and British self-funded volunteers who go by the name of ‘Intercontinental Archaeology.’ “The USF are specialised in the 3D and digital documentation of archeological sites and have already created a 3D model of the entire Domvs site for us. The plan is for us to build a virtual website whereby online visitors can view what is happening during the excavations on a daily basis as we upload 3D images of the artefacts we find and the trenches we excavate. Hopefully, this will generate interest and finances too.’ David Cardona elucidates.

By the second century AD, the Domvs was past its heyday, as two hastily patched up jobs on the mosaic floors attest. Simultaneously a few, smaller and inferior houses were constructed at the back of the present site where a baby’s bone rattle was discovered. Towards the end of the third century AD, the Domvs appears to have been abandoned altogether. “We are not sure if the Domvs had been subdivided into smaller units as we don’t have enough information. We are currently trying to identify cuts in the stone to get a clearer picture.” Cardona explains.

With luck, the excavations will help throw light on some of the missing pieces in the puzzle and map more topography to the buried ancient town of Melite.

By Warren J. Bugeja, Executive Communications, Heritage Malta

Latest News

Press Releases | 19th April 2024

A Vibrant Special Opening at Fort Delimara

Press Releases | 8th April 2024

Objects Missing From the Grand Master’s Palace