Caught up in the sweeping events of 1798, the lives of three Maltese men of the enlightenment are inextricably linked to Napoleon’s career trajectory.

Caught up in the sweeping events of 1798, the lives of three Maltese men of the enlightenment are inextricably linked to Napoleon’s career trajectory.

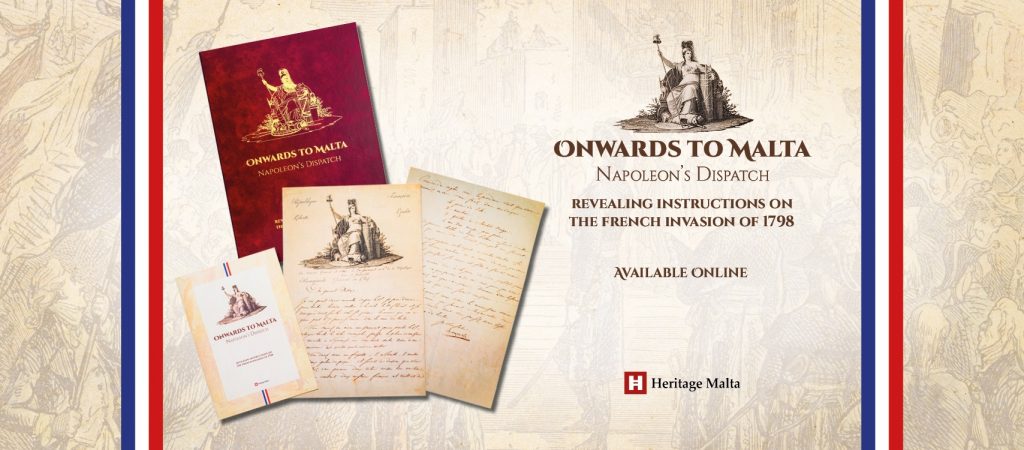

The recent acquisition by Heritage Malta of a letter, annotated and signed by the Commander in Chief of the French Army of the Orient ordering the invasion of Malta, focuses the spotlight back on the men who helped sow the seeds of Maltese nationhood. It is also the subject of an exciting Heritage Malta documentary which is currently in production illustrating the importance of this often overlooked period in our history.

The recent acquisition by Heritage Malta of a letter, annotated and signed by the Commander in Chief of the French Army of the Orient ordering the invasion of Malta, focuses the spotlight back on the men who helped sow the seeds of Maltese nationhood. It is also the subject of an exciting Heritage Malta documentary which is currently in production illustrating the importance of this often overlooked period in our history.

The eternal city which hosted Abate Mikiel Anton Vassalli in 1785 was already a “dream of the past”. According to historian Adrian Scerri, “Pope Pius VI had inherited a weak papal seat, rampant with nepotism” enfeebled by internal strife with the Jesuit faction and interference from the monarchies of Europe. But for Vassalli, who hailed from the tiny village of Ħaż-Żebbuġ, Rome was still the centre of Christian civilisation, of tumultuous crowds, cathedrals and clanging bells. Vassalli, whose family had bequeathed him some money to be able to finance his studies, attended University where he studied Semitic languages.

Influenced by enlightened men of his time, whose books at times were banned by the Church, Vassalli soon abandoned his clerical calling and instead became a convert to the ideals of the enlightenment. The teaching of these enlightened men was soon influencing Vassalli’s writings, as can still be gleaned from the introduction to his ‘Lexicon’.

In Rome, the linguist and philosopher published several books on the Maltese language. His books were printed by ‘Propaganda Fide’, one of the foremost printing presses in the world at the time, possessing all the type faces for bibles required by the Pope and for which Vassalli created new letters, thereby catering for the Maltese alphabet.

Lauded as the ‘Father of the Maltese Language’, Mikiel Anton Vassalli set out guidelines for the Maltese language, which had previously been penned phonetically in Italian script, to henceforth be written according to clear and logical rules based on a root form. His grammar tenets are still being taught in schools today.

Vassalli envisioned that Maltese could become the language of political life, used in law courts and schools. The dedication in his Lexicon is not to some knight, as was the custom of the time, but ‘alla Nazione Maltese’ (to the Maltese Nation). Vassalli was thanking the Maltese people for keeping the language alive. Consequently, this dictionary belongs to the people and language becomes the medium through which a nation can arrive at a full consciousness of itself.

![]() Vassalli outlined his ideas on education, which had hitherto been confined to the children of aristocrats. Vassalli, who was a fervent supporter of universal education, suggested that in the absence of schools, the many chapels dotted around the countryside of the Maltese islands could be used for such purpose, and he even made provisions for the salaries of headmasters and teachers.

Vassalli outlined his ideas on education, which had hitherto been confined to the children of aristocrats. Vassalli, who was a fervent supporter of universal education, suggested that in the absence of schools, the many chapels dotted around the countryside of the Maltese islands could be used for such purpose, and he even made provisions for the salaries of headmasters and teachers.

By 1795, Vassalli had met and was living in the same house as Elia Pace in Palazzo Spinelli in Piazza Venezia. Pace was a Maltese lawyer and political activist with republican sympathies who had been exiled by the Order of St. John for the second time. Fired by French revolutionary ideals which were destabilizing the Ancien Regime, Pace was responsible for planting the tree of liberty in Piazza del Campidoglio on the same day that the French arrived at the gates of Rome in February 1798. The act was one symbolising ‘freedom from an oppressor’ and Napoleon was at first welcomed by the Romans as a liberator. Pace was rewarded for his efforts by being appointed criminal judge and later Minister of the Interior for the new Republican Government of Rome. Meanwhile Vassalli, hearing the French were almost on Rome’s doorstep, had fled since he did not want to actively participate in politics. He did so despite the fact that the indices to his Lexicon were still in press.

Back in Malta Vassalli found himself reluctantly embroiled in a revolution, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. His intention upon returning had been to continue publishing books, but according to Fortunato Panzavecchia, the prevailing attitude of the time was that if one wrote books then he was a politician. Approached by Maltese Jacobites who wanted to form a political party and required someone to represent them, he was unaware that he would be implicated in a plot to remove Grandmaster de Rohan and supplant him with Hompesch.

In 1797, the Order of St. John found itself in straightened circumstances. Initially it had tried to sympathise with the revolution and even contributed funds, notwithstanding that the Order, comprising mainly aristocrats, was at odds with the enormous power being bestowed upon the bourgeoise. Unfortunately, the Order of St. John financed the flight of the Royal Family from Paris, and after they were apprehended at Varennes, the revolution retaliated with the confiscation of the Order’s lands in France. When the king was beheaded in 1793, the order set up a ‘Congregazione Criminale di Stato’ to exile anyone suspected of sympathising with the French revolutionary ideals. Zappala, a Sicilian, was one of those first tried and exiled for stating that subjects of a country not their king should be running it.

In 1797, the Order of St. John found itself in straightened circumstances. Initially it had tried to sympathise with the revolution and even contributed funds, notwithstanding that the Order, comprising mainly aristocrats, was at odds with the enormous power being bestowed upon the bourgeoise. Unfortunately, the Order of St. John financed the flight of the Royal Family from Paris, and after they were apprehended at Varennes, the revolution retaliated with the confiscation of the Order’s lands in France. When the king was beheaded in 1793, the order set up a ‘Congregazione Criminale di Stato’ to exile anyone suspected of sympathising with the French revolutionary ideals. Zappala, a Sicilian, was one of those first tried and exiled for stating that subjects of a country not their king should be running it.

In the same year an exasperated Pope, who was now the Order’s only ally, ordered De Rohan for the fourth time to get rid of one of the most important personages of the 18th century in Malta. This was the incorrigible survivor, Gio Niccolò Muscat, attorney general to the Order. Muscat had risen from humble origins and with his aunt’s assistance managed to become a lawyer and later advisor to Rohan. Such was his power it was said that ‘Malta was in his hands.’

Another adherent of the enlightenment, Niccolò believed that church and state should be separated, a prevalent idea in Europe of the time, but a notion not very popular with the Pope. He felt strongly that the Inquisition, which had declined enormously in importance, should furthermore be limited to affairs of the faith. Criminal cases were to be tried in the civil law courts, the Castellania. Things came to a head during the case of Conti Fenech, who was being tried in three separate courts for the same offence, and Niccolo’s stance cost him his office.

Another adherent of the enlightenment, Niccolò believed that church and state should be separated, a prevalent idea in Europe of the time, but a notion not very popular with the Pope. He felt strongly that the Inquisition, which had declined enormously in importance, should furthermore be limited to affairs of the faith. Criminal cases were to be tried in the civil law courts, the Castellania. Things came to a head during the case of Conti Fenech, who was being tried in three separate courts for the same offence, and Niccolo’s stance cost him his office.

“Muscat loved Malta,” asserts Professor Frans Ciappara from the Institute of Baroque Studies. As Vassalli did, Muscat also referred to the ‘Maltese Nation’. His vociferous Apologia ‘A Favore dell’ Inclita Nazione Maltese’ was written in response to ‘Ragionamenti’ compiled by a certain Neapolitan lawyer Giandonato Rogadeo. In it, Muscat, counteracts Rogadeo’s denigration that the Maltese were Africans and not Europeans, with repeated examples to the contrary. “Look at our Churches, our libraries, our lawyers, our clergy, our artists and mathematicians’ Muscat states. ‘Even the Gods of the sea (the British Fleet) praise Maltese sailors’ he goes on to add,” Professor Ciappara enthuses.

When Napoleon arrived in Malta in 1798, after instructing General Desaix to ‘assemble the armies, impound ships, arm them’ in his letter of 4th May, Muscat advised Grandmaster Hompesch to surrender. He was present on Napoleon’s ship L’Orient as part of the delegation negotiating the Knights Hospitaller’s capitulation. Denounced a traitor by his compatriots, Muscat wrote another Apologia explaining that he had recommended that course of action only because the gates of Valletta were in the hands of French Knights, ready to defect. He wanted to ‘die under the King of Naples’, he insisted. Nevertheless, Muscat was appointed President of the Civil Courts during the French occupation.

The day after landing, Napoleon encountered Vassalli where he had been incarcerated in Fort Ricasoli, referring to him as the ‘most learned man in Malta and oppressed by the Order of St. John.’ Vassalli was to be exiled under the British and lived in Spain and France where he dabbled unsuccessfully in the cotton industry.

The day after landing, Napoleon encountered Vassalli where he had been incarcerated in Fort Ricasoli, referring to him as the ‘most learned man in Malta and oppressed by the Order of St. John.’ Vassalli was to be exiled under the British and lived in Spain and France where he dabbled unsuccessfully in the cotton industry.

Towards the end of his life, when asked what effect the French Revolution and Napoleon had had on him, Vassalli replied that he had been ‘through no fault of my own, a victim of the revolution thrice over’, recounts Dr Olvin Vella, Lecturer at the University of Malta. Firstly, because he had lost his Cadre teaching Arabic in Rome, secondly because he had lost his homeland, and thirdly because he was forced to return to Malta as an indirect result of the reversal in Napoleon’s fortunes. He cynically referred to Napoleon as ‘buon-a-parte’. In Dr Vella’s words “Vassalli was an academic not a politician.”

Napoleon’s historic letter remains on display at the Museum of Archaeology in Valletta, free of charge to the general public until the end of November 2020. The three-page letter is part of Heritage Malta’s commitment to significantly increase the national collection, more so because “we don’t have many artefacts relating to the French period” says Noel Zammit Heritage Malta’s CEO. 40 replicas of Napoleon’s letter will be available on sale to the general public, with all proceeds going to the Community Chest Fund. The letters are available online on https://heritagemalta.org/shop/ and also at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta and the Ġgantija Temples in Gozo.

By Warren Joseph Bugeja, Heritage Malta

as featured in The Malta Independent of 23.11.20

warren.bugeja.1@gov.mt

Latest News

Press Releases | 19th April 2024

A Vibrant Special Opening at Fort Delimara

Press Releases | 8th April 2024

Objects Missing From the Grand Master’s Palace