An avant-garde spirit and early exponent of modern art, Giorgio Preca was born in Malta in 1909 but lived a great deal of his life in Rome, where he established a name for himself as an artist. His reputation as a pioneer of modernism in the local art scene was demonstrated in his trailblazing 1948 exhibition held at the Hotel Phoenicia in Floriana and cemented by another seminal exhibition held at the Hostel Verdelin, Valletta, in 1955. One year later, Preca had packed his bags for good and set off for Rome, where he married and settled down until his death in 1984.

An avant-garde spirit and early exponent of modern art, Giorgio Preca was born in Malta in 1909 but lived a great deal of his life in Rome, where he established a name for himself as an artist. His reputation as a pioneer of modernism in the local art scene was demonstrated in his trailblazing 1948 exhibition held at the Hotel Phoenicia in Floriana and cemented by another seminal exhibition held at the Hostel Verdelin, Valletta, in 1955. One year later, Preca had packed his bags for good and set off for Rome, where he married and settled down until his death in 1984.

His long time away from these shores accounts for the fact that despite exhibiting in Malta on fifteen occasions between 1933 and 1960, Preca is not a local household name. Heritage Malta’s exhibition ‘Giorgio Preca ta’ Malta,’ which will run between the 3rd of December and 27th of February at MUŻA in Valletta, the town where the artist was born, is set to change all that.

The interactive exhibition is the result of years of close collaboration and goodwill between Preca’s family and Heritage Malta. Some twenty-one paintings, four drawings, and six ceramic objects that Preca used for some of his still lifes, the majority of which have never been exhibited in Malta before, have been restored by Heritage Malta’s expert team of conservators and restorers prior to going on public display. The collaboration reflects a shared interest in acknowledging and honouring Giorgio Preca’s artistic legacy whilst providing accessibility to a new generation who might not be familiar with his oeuvre.

Following formative studies at the Malta Government School of Art, Preca’s love affair with Rome began where he travelled there with fellow artist Toussaint Busuttil and attended the Regia Accademia di Belle Arti. Preca soon graduated to the position of assistant professor at the British Academy, where he met Antonio Sciortino. At the outbreak of World War Two, Sciortino returned to Malta to take over the post of curator of the museum of fine arts vacated by Vincenzo Bonello, who was interned in Uganda on account of his alleged pro-Italian sympathies. Sciortino and Preca’s career trajectories were to overlap again. In 1944 Preca was employed as a restorer under Sciortino with the Museums Department, where he worked upon a few of the masterpieces from the National Collection. This association led indirectly to Preca’s second brush with controversy. Previously in a 1939 exhibition, a non-frontal female nude painted by Preca had caused an uproar requiring it to be partially covered with a curtain during the showing.

Following formative studies at the Malta Government School of Art, Preca’s love affair with Rome began where he travelled there with fellow artist Toussaint Busuttil and attended the Regia Accademia di Belle Arti. Preca soon graduated to the position of assistant professor at the British Academy, where he met Antonio Sciortino. At the outbreak of World War Two, Sciortino returned to Malta to take over the post of curator of the museum of fine arts vacated by Vincenzo Bonello, who was interned in Uganda on account of his alleged pro-Italian sympathies. Sciortino and Preca’s career trajectories were to overlap again. In 1944 Preca was employed as a restorer under Sciortino with the Museums Department, where he worked upon a few of the masterpieces from the National Collection. This association led indirectly to Preca’s second brush with controversy. Previously in a 1939 exhibition, a non-frontal female nude painted by Preca had caused an uproar requiring it to be partially covered with a curtain during the showing.

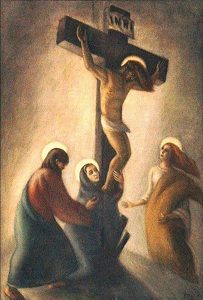

Having sustained a direct hit in the war, a few paintings, including the notable 16th-century altarpiece within Stella Maris Parish Church in Sliema, were damaged. Sciortino recommended Preca restore them, which resulted in a commission of a crucifixion-scene themed altarpiece a couple of years later by one of its parishioners. Unfortunately, Preca’s modern rendering of the subject seemed to affront the Baroque idiom still prevalent on the islands, and upon the patron’s passing away, Archbishop Gonzi was petitioned to banish the offending painting to the Bir-id-Deheb church in Żejtun where it remains today.

Having sustained a direct hit in the war, a few paintings, including the notable 16th-century altarpiece within Stella Maris Parish Church in Sliema, were damaged. Sciortino recommended Preca restore them, which resulted in a commission of a crucifixion-scene themed altarpiece a couple of years later by one of its parishioners. Unfortunately, Preca’s modern rendering of the subject seemed to affront the Baroque idiom still prevalent on the islands, and upon the patron’s passing away, Archbishop Gonzi was petitioned to banish the offending painting to the Bir-id-Deheb church in Żejtun where it remains today.

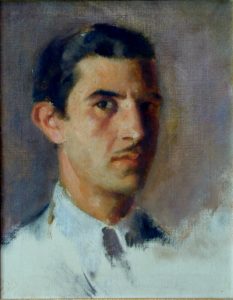

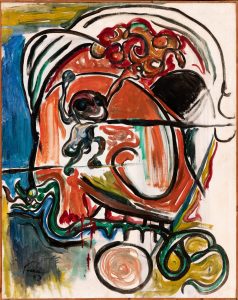

Giorgio Preca’s evolution from academic line and form to expressionism is evident when comparing traditionally executed portraits of Toussaint Busuttil or that of Grandmaster Fra Ludovico Chigi Albani, with the highly abstract oil-on-canvas self-portrait, painted much later in 1953 and acquired by Heritage Malta in 2019. One style brought in commissions and a livelihood, and the other a means of self-experimentation with contemporary themes and identification with artistic movements on the continent.

His vibrant and colourful still lifes are defined in bold, black contour lines, and are an expression of his inner vision. A man with his finger always on the pulse of his times, the subject material of Preca’s 1952 Rome exhibition ‘Inhabitants of the Moon Series’ consisted of aliens and dragons, a topical but still relatively avant-garde theme.

In 1958 Preca, was invited by the Italian government to exhibit his works at the Venetian Biennale within the Italian Pavilion dedicated to the foreign artists living in Rome. As his international reputation grew, similar invitations were extended to exhibit at the Commonwealth Centre in London.

In 1958 Preca, was invited by the Italian government to exhibit his works at the Venetian Biennale within the Italian Pavilion dedicated to the foreign artists living in Rome. As his international reputation grew, similar invitations were extended to exhibit at the Commonwealth Centre in London.

Modern art is not just experimental in style but also in technique, which may pose something of a challenge for conservator-restorers. In spite of his academic training and his stint as a restorer, Preca prioritised his artistic expression over technical know-how, layering his canvases in thick impasto application of paint which over time resulted in deformations in the underlying canvas. This necessitated a careful restoration intervention, a precise balancing act that involved respecting the authenticity of the original work of art, the immediacy of its colour and form, whilst repairing the damage caused to the painting over time, and preventing further deterioration.

Most canvases were strip-lined and stabilised using a new auxiliary stretching frame. Similar consolidation measures were also employed to counteract oxidation of the cellulose fibres caused by excessive use of binding materials such as poppy and linseed oil and varnishes, thereby further weakening the canvas.

Most canvases were strip-lined and stabilised using a new auxiliary stretching frame. Similar consolidation measures were also employed to counteract oxidation of the cellulose fibres caused by excessive use of binding materials such as poppy and linseed oil and varnishes, thereby further weakening the canvas.

The state-of-the-art Preca exhibition represents another milestone in Heritage Malta’s mission to make art more accessible. It follows fast on the heels of Mattia Preti’s ‘Boethius and Philosophy’ return to Malta and the recent exhibition of 13 loaned masterpieces at MUŻA. The use of the preposition ‘of’ in the title of the exhibition reclaims Giorgio Preca as a child of Malta and pays homage to his far-reaching often unacknowledged influence on the local art scene.

By Warren Bugeja, Executive Communications, Heritage Malta

As published in the Times of Malta on December 21, 2021

Latest News

Press Releases | 19th April 2024

A Vibrant Special Opening at Fort Delimara

Press Releases | 8th April 2024

Objects Missing From the Grand Master’s Palace

Up Next

News | 20th December 2021